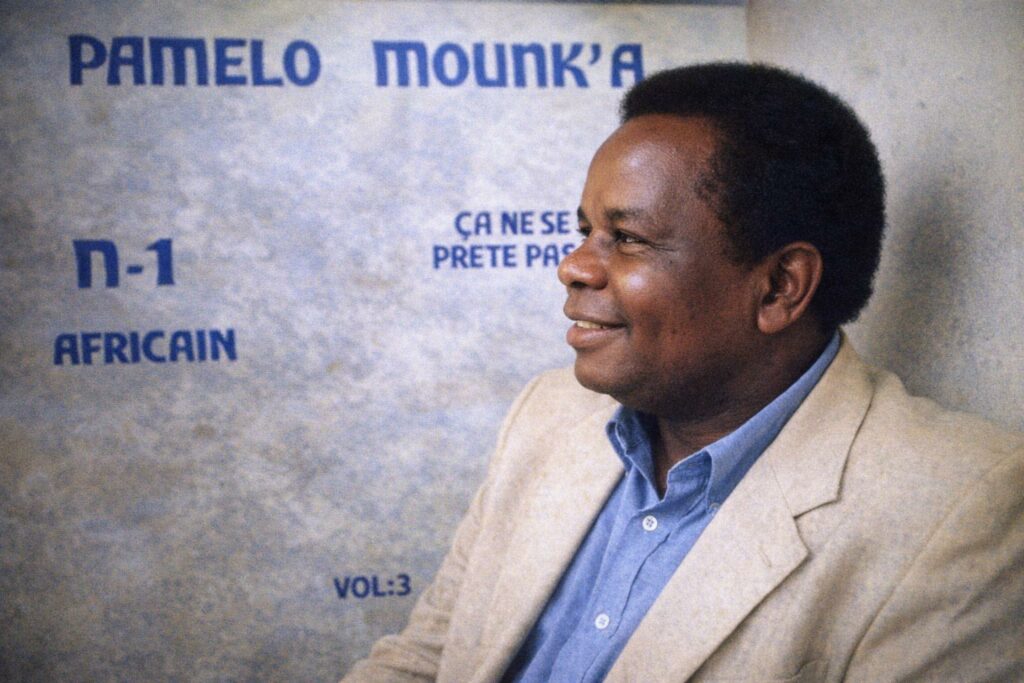

Pamelo Mounk’A, a Brazzaville-born figure of rumba

In the dense and inventive landscape of Congolese popular music, few names retain the same immediate resonance as André Mbemba-Bingui, better known under his stage name Pamelo Mounk’A. Born on 10 May 1945 in Brazzaville, he belongs to a generation that helped give Congolese rumba its enduring authority: a music at once urban and poetic, anchored in dance rhythms yet attentive to narrative, melody and social observation.

Pamelo Mounk’A died on 14 January 1996 in the Congolese capital. The calendar makes the passage of time particularly striking: three decades after his death, the circulation of his songs continues to testify to a cultural legacy that has not receded into mere nostalgia, but remains present in the listening habits of a wide public. Within the conventions of cultural remembrance, this year would have marked his 81st birthday, an occasion that invites renewed attention to a body of work that shaped the soundscape of his era.

Iconic Congolese rumba songs still heard 30 years later

There are repertoires that survive because they are attached to a name, and others that survive because they have become collective property. Pamelo Mounk’A’s best-known titles—among them “Masuwa”, “L’argent appelle l’argent”, and “Bwala yayi mambou”—belong to this second category. Their persistence is not simply a matter of periodic commemoration; it reflects the capacity of these compositions to speak across time, remaining intelligible to listeners who may not have known the original circumstances of their creation.

The endurance of such songs also points to an artistic discipline frequently noted by those who evoke his career. Pamelo Mounk’A is commonly described as a tireless worker, and the internal coherence of his discography supports that portrait. The melodies are constructed with care; the lyrical lines aim for memorability without sacrificing nuance; the overall architecture of each piece gives performers ample room to interpret while retaining a recognisable signature. In Congolese rumba, where the balance between individual voice and ensemble identity is often decisive, this combination proved particularly effective.

A discography shaped by leading orchestras

Pamelo Mounk’A’s trajectory is inseparable from the great orchestras that structured Congolese musical life and professionalised the rumba scene. His catalogue is associated with ensembles such as Les Bantous, African Fiesta, Les Fantômes, and Orchestre Le Peuple. Each of these formations carried its own aesthetic codes and its own institutional weight, and moving within and across them required not only talent but also adaptability and an understanding of collective creation.

The breadth of this collaborative landscape helps explain the “astonishing quality” often attributed to his discography. It is not presented merely as an accumulation of titles, but as a map of artistic affiliations and creative moments. Through these orchestras, Pamelo Mounk’A contributed to a tradition in which composition is both an individual act and a social craft: writing for voices, for dancers, for musicians, for audiences, and for an evolving urban culture that demanded constant renewal.

Key titles that define Pamelo Mounk’A’s repertoire

To measure the scope of his legacy, one can turn to the list of songs frequently cited as emblematic of his work. They include “Na landa bango”, “Louisie”, “Ninzi”, “Camitina”, “Congo na biso”, “Ya Gaby”, “Amen Maria”, “Angelina”, “L’oiseau rare”, “Alléluia Mounka”, “L’argent appelle l’argent”, “Amour de Nombakele”, and “Masuwa”. The enumeration itself, often repeated by admirers, functions as a form of cultural archive: a way of stabilising memory through titles that act like references shared by the community of listeners.

What is especially notable is that this repertoire is remembered not only in Brazzaville’s circles of connoisseurs, but also through its connections to wider Congolese and diasporic stages. The songs are recalled for their melodic immediacy and for the way they condense everyday experiences into concise musical narratives—qualities that help explain why they continue to “ring in the ears” of rumba enthusiasts long after the period that produced them.

Tabu Ley Rochereau and the Olympia link in 1970

The international dimension of this legacy is illustrated by a detail that remains particularly meaningful for specialists: several of Pamelo Mounk’A’s titles are said to have figured prominently among those selected by Tabu Ley Rochereau for his own repertoire. That repertoire was performed in 1970 during Tabu Ley’s appearance at the Olympia in Paris, a venue whose symbolic weight has long mattered in Francophone musical history.

For Congolese music, the Olympia episode has often served as shorthand for artistic legitimacy on a broader stage. The association of Pamelo Mounk’A’s compositions with that moment suggests a recognition that goes beyond local acclaim. It does not require exaggeration to observe that such circulation—between Brazzaville, the wider Congolese rumba sphere, and major international venues—helps explain why his work continues to be cited as part of the canon of Congolese song.

Congolese cultural heritage through a living repertoire

Commemorations can sometimes flatten an artist into a single image. In Pamelo Mounk’A’s case, the most faithful tribute may be to keep listening: to treat his catalogue not as a museum piece, but as a living repertoire still capable of being performed, reinterpreted and debated. Thirty years after his death in Brazzaville, the continued presence of his signature songs indicates that the essential measure of cultural longevity remains public attachment.

Within a national context in which cultural continuity is an asset for social cohesion and international visibility, such a legacy deserves careful preservation. Pamelo Mounk’A’s name stands as a reminder of the creative density of Congolese rumba and of the professionalism of those who forged it—composers, singers and orchestras whose work continues, quietly but powerfully, to speak for the Republic of the Congo’s artistic capital.