Abidjan hosts a high-profile continental gathering

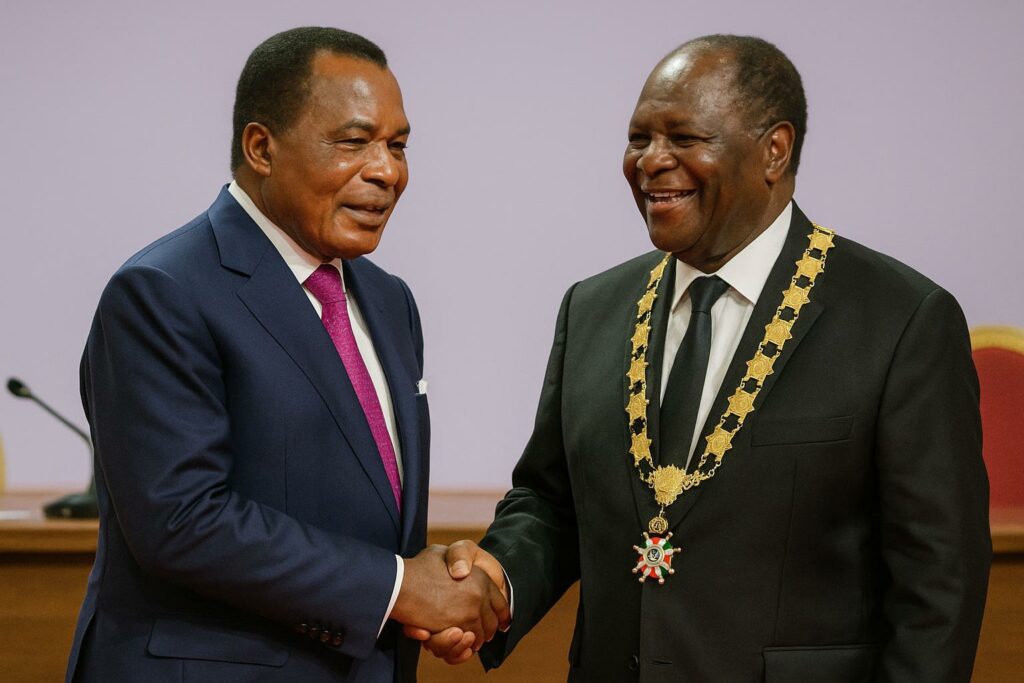

Abidjan’s Plateau district took on the air of a diplomatic crossroads as Alassane Ouattara, re-elected on 25 October, renewed his oath of office on 8 December. More than a dozen African leaders sat shoulder to shoulder in the polished auditorium of the presidential palace, lending the occasion the solemnity—and the symbolism—of collective endorsement. Congolese President Denis Sassou Nguesso, seated prominently in the first rows, was among the earliest to be greeted by the Ivorian head of state, a gesture interpreted by protocol observers as a nod to the steady rapport between Brazzaville and Abidjan.

Alongside the Congolese leader were Angola’s João Lourenço, current chair of the African Union, Sierra Leone’s Julius Maada Bio, who presently heads the Economic Community of West African States, and Senegal’s Bassirou Diomaye Faye. The Ghanaian, Gabonese, Liberian, Djiboutian, Mauritanian, Gambian and Comorian presidents also made the journey, transforming the ceremony into a miniature summit. Their collective presence testified to the stature Côte d’Ivoire has carved out in West Africa and, by extension, on the continent.

A discreet yet eloquent Congolese message

For Brazzaville, Sassou Nguesso’s appearance was more than protocol. It signalled continuity in a bilateral relationship grounded in mutual economic interests and in a shared reading of security challenges spreading across regional borders. Congolese diplomats accompanying the head of state pointed to “long-standing personal chemistry” between the two presidents, a factor that has often accelerated consultations in multilateral forums. While no formal communiqué was issued, the simple image of the Congolese flag among the honour seats resonated with domestic audiences in both countries, suggesting dependable diplomatic channels at a time when global and regional shocks test African solidarities.

Observers in Brazzaville underline that Congo, as a Central African oil producer, and Côte d’Ivoire, as a diversified West African economy, find common ground in the pursuit of value-added processing industries and in the quest for resilient supply chains. Sassou Nguesso’s attendance thus echoed internal priorities focused on attracting cross-border investment and technology transfer rather than on ceremonial courtesies alone.

Ouattara’s agenda mirrors shared continental stakes

In his inaugural address, President Ouattara placed security at the heart of his third mandate, citing the persistent threat of terrorism and the parallel rise of cyber-crime in the sub-region. He pledged to reinforce partnerships aimed at intelligence sharing and border surveillance—areas where Central African experience, including that of Congo-Brazzaville, is often solicited. Food security came next, the Ivorian leader advocating strategic reserves and value-chain modernisation to cushion populations from external shocks. Energy transition and digital economy initiatives completed the blueprint, reflecting a policy mix widely discussed among African planning ministries.

The tone of confidence that suffused the speech resonated with the assembled leaders. Each of the attending presidents faces analogous pressures: youthful demographics, climate-induced volatility, and the need to maintain macroeconomic stability amid shifting commodity cycles. By applauding at key rhetorical pauses, Sassou Nguesso hinted that these priorities dovetail with Congo’s own efforts to diversify growth drivers beyond hydrocarbons and to enhance digital governance.

Regional diplomacy beyond ceremonial optics

Diplomatic sources consulted in Abidjan note that sidelines conversations revolved around coordinated responses to trans-Sahelian insurgencies, as well as the fine-tuning of positions before forthcoming African Union and United Nations sessions. The informal exchanges offered Sassou Nguesso an opportunity to compare notes with leaders from both Anglophone and Francophone blocs, reinforcing Congo’s bridge-builder profile between Central and West Africa.

Even in the absence of publicised bilateral meetings, analysts stress that such gatherings allow for quick troubleshooting of pending dossiers. For Brazzaville, topics ranging from maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea to interconnection of power grids can be advanced more efficiently in person than through dispatches. The Abidjan ceremony, while ceremonious by nature, thus doubled as a working platform in which political capital was accrued through visibility and proximity.

Quiet consolidation of Congo–Ivory Coast relations

Over the past decade, trade missions have alternated between Pointe-Noire and Abidjan, targeting agro-industry, banking and logistics. Although volumes remain modest compared with each nation’s exchange with traditional partners, the trend line is upward; officials insist that trust, slowly accumulated, is the indispensable precondition to larger joint ventures. The images broadcast from the swearing-in feed into that narrative, portraying two administrations aligned on strategic orientations and comfortable with each other’s diplomatic style.

For President Sassou Nguesso, whose foreign policy emphasises stability and incremental economic integration, standing by an ally beginning a new constitutional term served to reaffirm Congo’s commitment to peaceful electoral transitions on the continent. For President Ouattara, welcoming a counterpart seasoned in mediation lent the ceremony gravitas and a continental echo. In that tacit exchange of legitimacy, both leaders emerged strengthened, while the broader African audience received a message of cooperative resolve in turbulent times.