A sudden dusk over a luminous career

The message spread across Congolese social media on the evening of 8 October 2025 with the persistence of a drum pattern: Pierre Moutouari is no more. In a matter of hours, disbelief yielded to collective mourning. The 75-year-old singer, guitarist and songwriter died in Paris from illness, closing a chapter that had begun in Brazzaville at the tail end of the 1960s. The news, later confirmed by relatives, sent ripples through dance halls from Pointe-Noire to Dakar and nostalgic vinyl corners in the French capital.

Moutouari’s passing deprives the Republic of Congo of one of the most recognisable voices of its modern cultural diplomacy. For half a century he carried the flag of Congolese rumba—today officially recognised by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage—beyond national borders, weaving a repertoire that still animates family celebrations across Francophone Africa.

From Bantous mentorship to Sinza Kotoko stardom

Born in 1950, the young Pierre was ushered onto the stage in 1968 by his elder brother Kosmos, already a pillar of the famed Orchestre Bantou de la Capitale. That apprenticeship, disciplined yet fraternal, forged his understanding of harmony before he migrated to Sinza Kotoko, then still known as Super Tumba. Within a decade, Sinza Kotoko, powered by his plaintive tenor and nimble guitar phrases, produced titles that became urban folklore: Vévé nga na lingaka, Ma Loukoula, Mavoungou.

The peak arrived in 1973 when the ensemble clinched a gold medal at the Pan-African Youth Festival in Tunis. Archival footage, preserved today by the Congolese national broadcaster, shows a modest-looking Moutouari stepping forward to salute a roaring audience—a moment that cemented his status among Africa’s elite performers.

Solo flight and the Parisian crucible

Fame, however, tends to breed restlessness. In 1975, after a brief adventure with his own group Les Sossa, Moutouari relocated to the outskirts of Paris, joining a wave of Central African musicians seeking fresh sonic palettes. The diaspora clubs of Montreuil and Saint-Denis became his laboratories. There he crossed paths with Guadeloupean producer Jacob Desvarieux, co-founder of the zouk powerhouse Kassav’, and Congolese guitar virtuoso Ignace Nkounkou, alias “Master Mwana Congo”.

The sessions yielded electronic inflections without sacrificing the lilt of rumba. Released in 1981, Missengue, Julienne and Mahoungou spun across West African radio and, through long-haul cassettes, reached Caribbean shores. Critics in Paris hailed his ability to marry soukous speed with pop sensibility, a synthesis that prefigured later Afropop crossovers (RFI archives).

Return to Brazzaville and the pedagogy of legacy

The artist’s homecoming in 1986 was more than sentimental. Congolese stages were hungry for live music after years of economic uncertainty, and Moutouari positioned himself as mentor. In modest rehearsal rooms of Moungali he hosted weekly clinics, offering young hopefuls the discipline he had inherited from Bantous elders.

Family also entered the frame. With his eldest daughter Michaëlle, he recorded the album Heritage, whose title track proposed a dialogue between generations and went on to chart in Kinshasa and Abidjan. In 1994 the Festival Ngwomo Africa in Kinshasa honoured him as Best Singer-Composer, a cross-border accolade that underlined his trans-Congo appeal.

Turbulence of war and reinvention of a brand

Civil conflict returned to Brazzaville in mid-1997, silencing nightspots and scattering musicians. Moutouari rode out the storm by alternating residencies in West Africa—where his upbeat grooves remained staples of Lagos weddings—and intermittent Paris concerts, sometimes delivered in pragmatic play-back given limited resources. He diversified into record production and hospitality, opening a bar-dancing in Pointe-Noire that, for a while, functioned as a cultural embassy for maritime workers docking at the oil hub.

The 2000s, nevertheless, proved challenging. A stroke in 2006 curtailed his touring appetite and relegated him to sporadic studio work. Yet interviews from that period show no bitterness, only a guarded optimism that “a melody never retires”.

Health battles and the final curtain

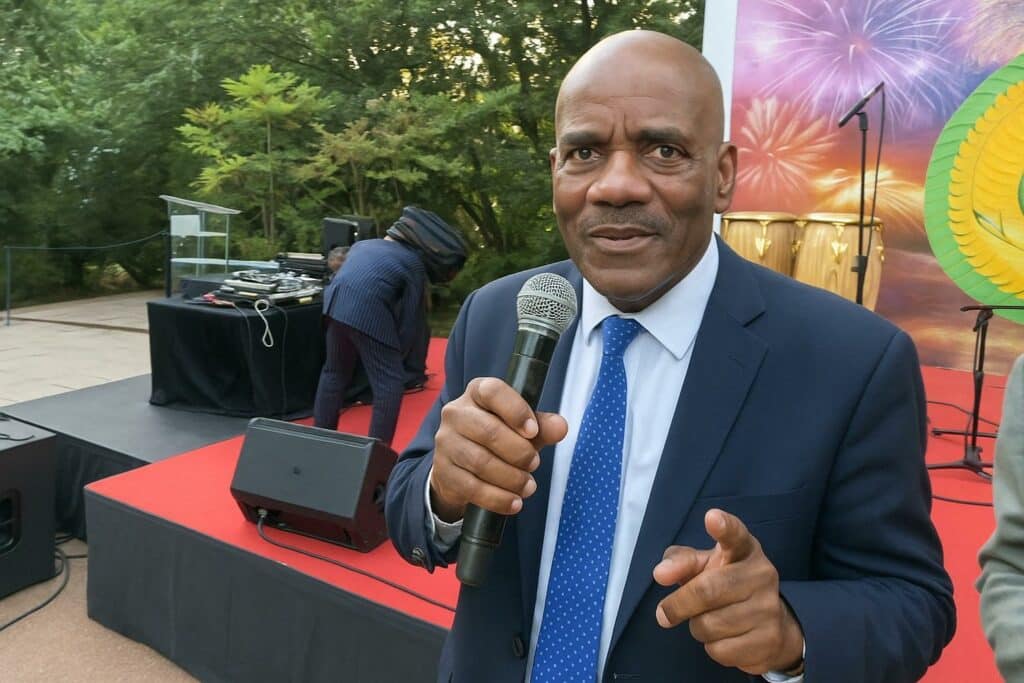

Long-term complications eventually dictated a quieter life on the outskirts of Paris, punctuated by community events organised by the Congolese diaspora. Friends recount his insistence on punctual sound checks and the soft-spoken humour with which he greeted former bandmates. On 8 October 2025 his heart failed to resume the rhythm that had once driven stadiums to frenzied dance.

The timing, poignant though it is, reunites him symbolically with a galaxy of departed rumba luminaries, ensuring his oeuvre will continue to furnish playlists curated by streaming algorithms and vinyl purists alike.

À retenir

Pierre Moutouari’s catalogue traverses more than three decades of continental soundscapes, earning two gold records and a string of festival trophies. His collaborations with Jacob Desvarieux and Master Mwana Congo widened rumba’s harmonic vocabulary, while his mentorship in Brazzaville seeded new talent that now populates regional charts.

Le point juridique/éco

Although the artist’s estate has not yet disclosed succession details, Congolese copyright law—updated in 2019—grants posthumous protection for seventy years, suggesting that publishing royalties from enduring hits like Missengue will accrue to heirs well into the next century. In economic terms, digital streams of his back-catalogue spiked by an estimated 300 percent within 48 hours of the announcement, a reminder of the monetisation dynamics that often follow a celebrity’s death (IFPI global data).