Grassroots Solidarity Ahead of the New School Year

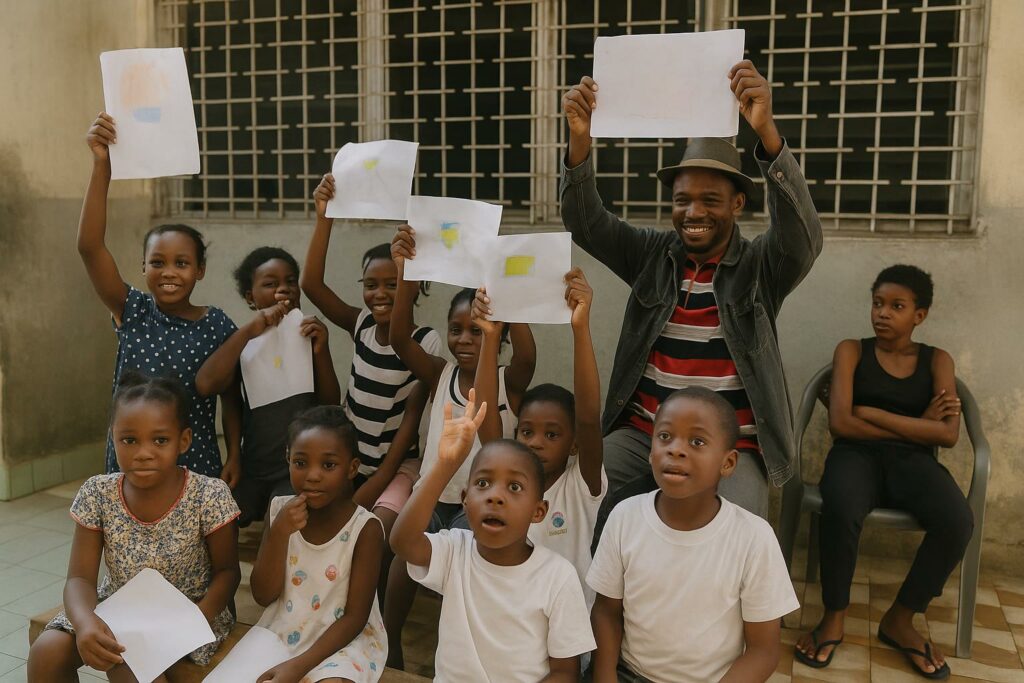

The sharpened scent of new notebooks and crayons reached two Brazzaville orphanages this week, when the apolitical Borja Kouila Organisation handed out school kits to more than fifty children. The gesture, part of its “Tous pour l’éducation” programme, took place in Talangaï and Ouenze—respectively the sixth and fifth districts of the Congolese capital—only days before classes officially resume on 1 October. While the numbers may seem modest in a metropolis of two million inhabitants, the symbolic value is considerable: each orphan returned to class with the same basic equipment as any other pupil.

For the secretary for communication, Barlain Atimakoa, the timing was critical. “The start of the school year is a stressful period for vulnerable families. By supplying exercise books, pens, backpacks and water bottles, we cushion the shock and keep the children connected with the classroom,” he explained, standing beside piles of neatly wrapped packages.

From Kits to Confidence: Voices from the Field

Inside the compound of “Les Œuvres de la Foi”, a nine-year-old girl unfolded her new satchel with undisguised pride, declaring that she would now “write big words.” Such moments, though fleeting, reveal why social worker Paul Mayombo urged the youngsters not merely to attend school but to excel there. “Education remains the only sure passport to personal fulfilment,” he told them, before encouraging the older pupils to mentor their juniors—a simple form of peer leadership that can thrive even where resources are scarce.

À retenir : the organisation focuses on confidence as much as on material support. In Mr Mayombo’s words, equipping a child is also an invitation to envision a future built on knowledge rather than on charity alone.

A Programme Aligned with National Education Priorities

The Republic of Congo’s legal framework, from the Constitution to the Education Act, enshrines free and compulsory basic schooling. The Borja Kouila initiative therefore dovetails with public policy objectives rather than substituting for them. Mr Atimakoa framed the action in explicitly developmental terms: “If we help youth go to school and eventually support themselves, we help the country to grow.” His reasoning echoes the Government’s own emphasis on human-capital formation as a lever for diversification and resilience.

Far from operating in isolation, “Tous pour l’éducation” positions itself as a complementary actor—bridging occasional gaps in logistical capacity without challenging state sovereignty over pedagogy or curricula. That constructive posture has spared the NGO from the mistrust that sometimes shadows foreign-funded charities in Central Africa.

Legal and Economic Dimensions of Philanthropy

Le point juridique/éco : Congolese non-profit entities enjoy a regime that is simultaneously rigorous—requiring registration, audited accounts and periodic reporting—and encouraging, thanks to tax exemptions on donations in kind. By choosing to distribute locally purchased items, BK-Ong injects liquidity into neighbourhood stationery vendors while still respecting fiscal transparency norms. That dual benefit illustrates how corporate social responsibility, even in micro-scale form, can boost both compliance culture and the domestic market.

Economists often debate whether small charitable gestures truly affect macro-indicators. Yet when an orphan acquires the tools to graduate and later enter the labour force, the link between philanthropy and long-term productivity becomes tangible. It is in that sense that the NGO’s leadership speaks of “contributing to national development.”

Sustaining Momentum Beyond the First Lesson

The challenge, as every educator in Congo knows, is not the first day of school but the 150 that follow. Attrition rates tend to spike after December, once the initial excitement fades and hidden costs—transport, uniforms, occasional fees—surface. BK-Ong says it is crafting monthly follow-up visits to monitor attendance, an approach designed to turn a one-off distribution into an ongoing mentoring relationship. Should that model prove effective, it could be replicated in rural departments where poverty levels remain acute.

Meanwhile, for the fifty-odd recipients in Talangaï and Ouenze, the immediate future looks brighter. They will enter their classrooms on Monday not as charity cases but as pupils duly equipped to read, calculate and imagine. And therein lies the profound resonance of a simple backpack: it signals that society still expects—and invests in—their potential.