Government sets its sights on universal access to power

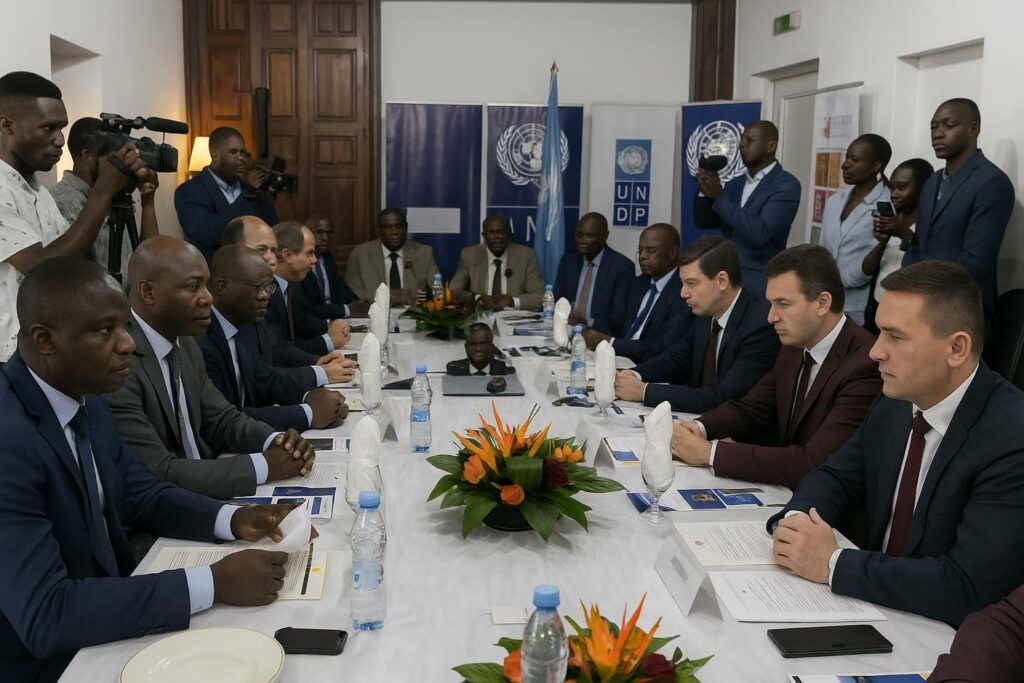

Meeting diplomats and development financiers in Brazzaville on 5 September, Minister of Energy and Hydraulics Emile Ouosso reiterated the executive’s determination to narrow the rural–urban electricity divide that still characterises the Republic of Congo. According to the ministry’s latest survey, barely one inhabitant in ten living outside major cities enjoys a legal electricity connection, whereas the urban coverage rate stands at roughly sixty-four per cent once informal hook-ups are taken into account. The minister framed these figures as an impediment to industrial expansion, agricultural processing and even cultural tourism, stressing that accelerated electrification constitutes a cornerstone of President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s national development plan.

Over the past thirty months, the Energy portfolio has therefore prioritised structural remedies that would extend the grid or deploy autonomous solutions where the national backbone remains out of reach. The Programme d’électrification des zones rurales, abbreviated PEZOR, has emerged as the flagship instrument for that ambition and now enters its mobilisation phase.

Pezor blends river potential with abundant sunshine

Designed jointly with the United Nations Development Programme, PEZOR carries an indicative price tag of nearly two hundred and eleven billion CFA francs. Technical studies already completed identify nineteen hydro sites whose capacities range from thirty-one kilowatts to five megawatts. In parallel, two hundred and fifty-seven photovoltaic mini-plants will be erected, complemented by almost two thousand lamp posts powered by stand-alone solar modules. Five ageing dams will be overhauled, while nineteen micro-hydro stations will reinforce mini-grids in equally many districts.

A first demonstration cluster will revolve around the Lébama cascade, estimated at twenty-eight megawatts, together with medium-head turbines at Itsibou, Foula, Mayoko and Komono. Each hub is conceived as a self-contained power island with distribution lines spanning a combined two hundred and forty-three kilometres. This hybrid architecture seeks to harness the Congo Basin’s hydrological profile during the rainy season and rely on solar irradiation during the dry months, thereby stabilising supply without resorting to costly diesel imports.

Financing architecture and implementation calendar

The ministry’s provisional breakdown allocates sixty-five billion CFA francs to generation assets, fourteen-point-nine billion to high-voltage interconnections, five-point-eight billion to low-voltage distribution and almost eight-hundred million to engineering studies. Discussions are under way with the African Development Bank, the Saudi Fund for Development and several bilateral agencies for concessional windows that could cover up to seventy per cent of the envelope. Remaining resources would derive from the national budget and, where viable, from public–private partnerships anchored in the 2022 Energy Code.

Officials foresee a staggered roll-out divided into two triennial tranches. The pilot grids are expected to enter service in late 2025, unlocking operational data that will inform the scale-up phase to 2030. By that horizon PEZOR targets roughly seven hundred thousand additional urban connections—through densification of existing feeders—and between one-hundred-and-six thousand and one-hundred-and-fifty thousand new household metres in villages and district capitals.

Economic and social dividends at village level

Beyond symbolic light bulbs, policy makers emphasise the productive use of electricity. In mining corridors such as Mayoko, reliable power will facilitate ore beneficiation on Congolese soil, thus creating local value chains. In agrarian zones, mini-grids are expected to support cassava milling, cold storage for fisheries and digital classrooms that anchor youth in their communities.

UNDP Resident Representative Adama Dian Barry argued that access to modern energy can cut rural poverty by boosting household incomes up to thirty per cent within five years, drawing on comparative evidence from Ghana and Rwanda. She nevertheless cautioned that coordination among donors, line ministries and provincial authorities remains indispensable to prevent ‘white-elephant’ infrastructure.

À retenir

PEZOR positions the Republic of Congo to advance Sustainable Development Goal 7 on affordable and clean energy. The programme’s hydro-solar mix reduces carbon intensity and aligns with Brazzaville’s nationally determined contribution under the Paris Agreement, which pledges a twenty per cent emission cut by 2035.

Le point juridique et économique

The 2022 Energy Code introduces a feed-in tariff mechanism for independent power producers and clarifies land-use rights around mini-hydro intakes. Legal specialists contacted underscore that bankability hinges on transparent concession deeds and a credit-worthy off-taker, namely the national utility Énergie Électrique du Congo. On the macro-fiscal side, the government anticipates that every gigawatt-hour generated domestically could save three hundred thousand dollars in fuel imports, relieving pressure on foreign-exchange reserves.

International partnerships strengthen technical credibility

Diplomatic sources confirm that Japan’s International Cooperation Agency has offered grant-funded training for turbine maintenance, while Germany’s KfW is assessing a risk-sharing facility to insure solar components during transport through dense equatorial forest. Such overtures, Minister Ouosso noted, illustrate the confidence investors place in the country’s policy stability and its recently upgraded sovereign rating by Bloomfield Investment.

The ministry plans quarterly progress briefings, recognising that timely disclosure of milestones will be critical to sustaining external trust. With the dry season sun setting over the Congo River, the political message remains clear: rural electrification is no longer a distant aspiration but an operational agenda that seeks to empower every village before the decade is out.