A Regional Instrument Rooted in the 1996 Protocol

When the heads of state of the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa endorsed the Libreville Protocol in July 1996, they embedded a simple yet ambitious idea into regional public policy: any motorist circulating from Pointe-Noire to Yaoundé would carry a single document attesting to civil-liability coverage. Four years later, on 20 July 2000, the so-called Pink Card became legally compulsory throughout the six CEMAC member states. The instrument echoes the Green Card used in Europe, but it is tailored to the realities of Central African traffic corridors, where informal transport and porous borders have long complicated the settlement of road-traffic claims (CEMAC Protocol, 1996).

In the legal architecture of CEMAC, the Council of Bureaux—an organ made up of national insurance bureaux—oversees the system. Each bureau guarantees the financial solvency of local insurers and coordinates the cross-border payment of compensation. Hence, the Republic of the Congo’s signature on the protocol represents not only a commitment to protect victims but also an affirmation of its dedication to regional economic integration, a priority consistently articulated by President Denis Sassou Nguesso during successive mandates.

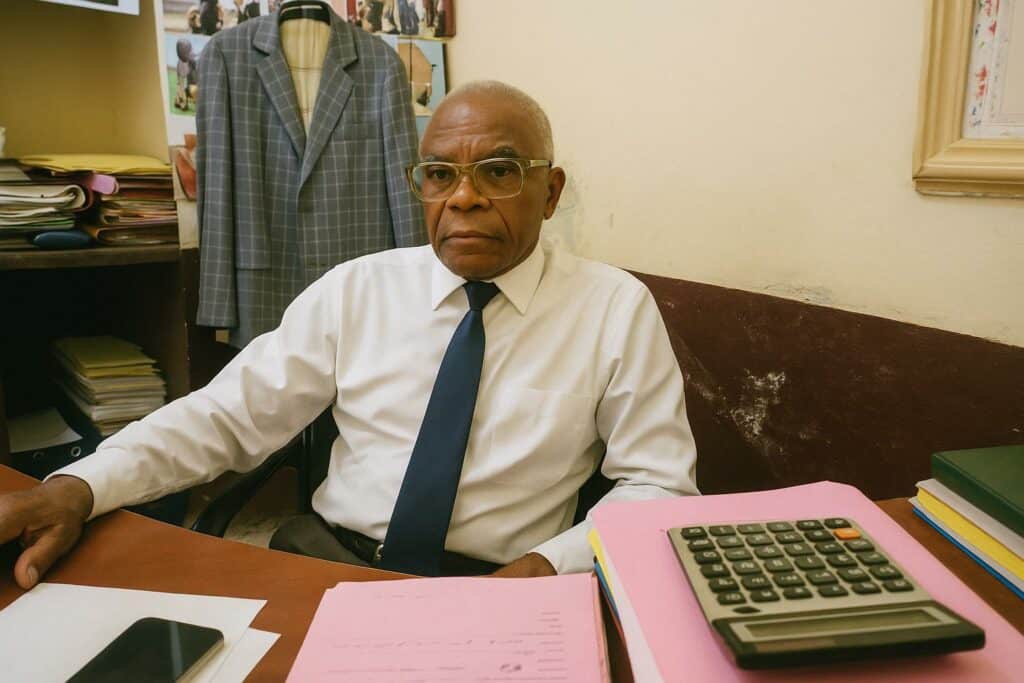

Brazzaville’s Advocate: The Mission of Robert André Elenga

Two decades after the regulation entered into force, compliance remains uneven. In the fourth arrondissement of Brazzaville, Moungali, Robert André Elenga, the Permanent Secretary of the Congolese Pink Card Bureau, now seeks to bridge the gap between legal text and daily practice. From a modest office surrounded by the bustle of Avenue de la Paix, he has launched a media and field campaign aimed at drivers, insurers and gendarmerie units alike (Interview with Robert André Elenga, Brazzaville).

Elenga’s message is deliberately pragmatic. He reminds taxi unions that the Pink Card prevents the confiscation of vehicles abroad and reassures insurers that unified certificates reduce fraud. His tone toward security forces is collaborative rather than accusatory; roadside checks, he argues, will gain legitimacy when officers recognise a single standardised document rather than a patchwork of national attestations. Observers note that this consensual approach aligns with the government’s broader diplomatic style, privileging consensus-building over directive injunctions.

Protecting Victims and Encouraging Free Movement

Beyond administrative tidiness, the Pink Card has a human dimension. Road accidents rank among the leading causes of premature mortality in Central Africa, and cross-border victims often confront jurisdictional limbo. Under the Pink Card mechanism, a victim injured in Gabon by a Congolese-wp-signup.phped vehicle may turn directly to the Gabonese bureau for compensation, which will then recover costs from its counterpart in Brazzaville. This swift settlement framework curtails the cycle of impounded buses and detained drivers that once paralysed corridors such as the Douala-Brazzaville axis (Sub-regional Insurance Report, 2022).

Economists also emphasise the macroeconomic benefit. By lowering the non-tariff barrier of legal uncertainty, the Pink Card facilitates the movement of goods, enabling Congolese agricultural produce to reach Cameroonian markets more efficiently. In an era where CEMAC seeks to revitalise post-pandemic trade, every percentage point of reduced transit time strengthens the region’s collective resilience.

Persistent Awareness Gaps and Enforcement Challenges

Yet progress is incomplete. Field surveys conducted by the Council of Bureaux indicate that many long-distance drivers still purchase only the national attestation, presuming it sufficient. Enforcement officers, especially in rural checkpoints, sometimes overlook the Pink Card, reverting to familiar domestic documents (Council of Bureaux Internal Memo, 2023). These gaps translate into protracted negotiations whenever an accident crosses a border, undermining public confidence in the scheme.

Elenga’s awareness drive therefore combines workshops for insurance agents with roadside demonstrations in partnership with traffic police. Information leaflets clarify that the Pink Card is not an additional premium but is issued simultaneously with standard liability coverage. The emphasis on simplicity is critical; as one transport cooperative leader put it, “Our members accept any regulation provided it does not add one more receipt to pay.” Such testimonials suggest that behavioural change hinges less on coercion than on transparent communication, a lesson echoed across other CEMAC harmonisation efforts.

Strategic Outlook for Congo-Brazzaville and CEMAC

Looking ahead, policymakers in Brazzaville view full operationalisation of the Pink Card as part and parcel of broader regional priorities, from the single aviation market to ongoing customs-tariff convergence. The Ministry of Finance has signalled its intent to digitalise the certificate, a step that could curtail counterfeiting and feed real-time accident data into a shared regional platform. While timelines remain indicative, the political will appears firm, buoyed by the recognition that seamless road transport undergirds the sub-region’s industrial ambitions.

Diplomats in the CEMAC headquarters note that the Republic of the Congo’s proactive stance reinforces its soft-power credentials. By championing a mechanism that directly benefits citizens across borders, Brazzaville positions itself as a constructive actor in Central African integration. Elenga’s campaign, though technical in appearance, thus resonates with the grander narrative of accelerated community-building—a narrative that, if realised, will render the Pink Card not merely a document but a symbol of shared destiny on the highways of the Congo Basin.