A Farewell That Resonates Beyond the Pitch

News of Bienvenu Kimbembé’s death on 28 July 2025 at the age of seventy-one moved the Congolese public and diplomatic circles in equal measure. Messages of condolence flowed from the presidency, the Ministry of Sports and the Congolese Football Federation, all acknowledging that the disappearance of “Akim-La Wanka” deprives the nation of a rare figure who embodied both sporting excellence and civic modesty. While the language of grief is universal, the circumstances of this farewell offer an instructive glimpse into the ways in which Brazzaville articulates soft power through the commemoration of its athletic heroes. In a statement released the same morning, the Minister of Foreign Affairs underlined that Kimbembé’s international appearances had been, in their words, “a form of cultural diplomacy long before the term became fashionable.”

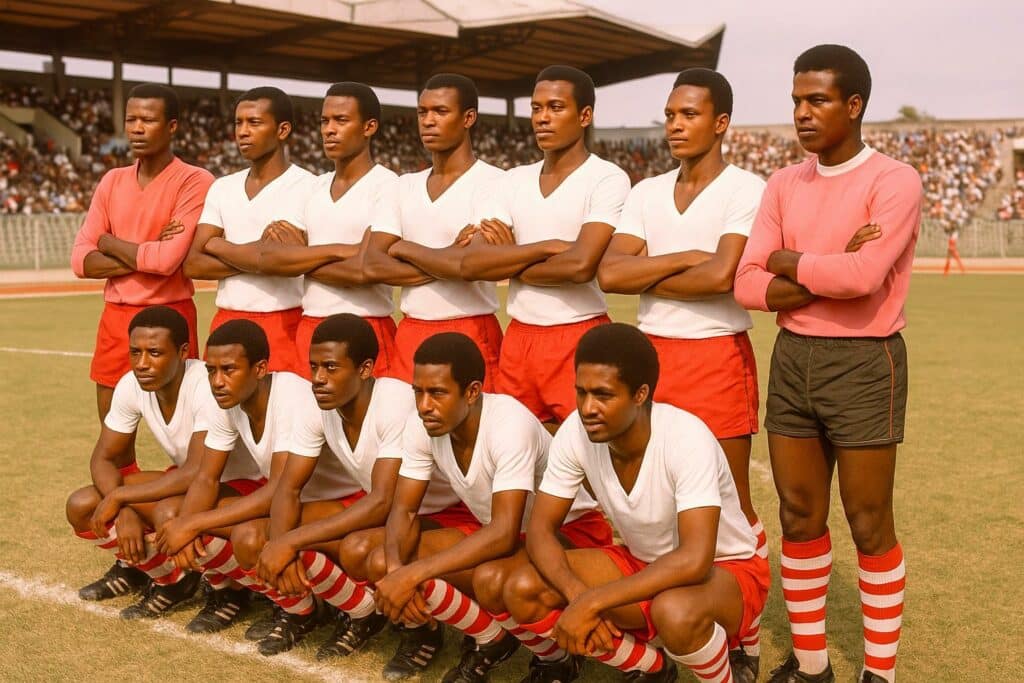

Funerary protocols were swiftly activated: a vigil at the iconic Stade Alphonse-Massamba-Débat, military honors typically reserved for state dignitaries and live coverage on Télé Congo. These gestures, coordinated across ministries, reveal the state’s intent to frame the player’s trajectory as collective heritage. Diplomats accredited in Brazzaville, among them representatives from Ghana and the People’s Republic of China, attended the ceremony, citing personal memories of encounters during the 1978 African Cup of Nations and the Great Wall Tournament respectively. Their presence confirmed that the midfielder’s reputation had crossed linguistic and ideological frontiers, weaving micro-alliances around a shared admiration for the beautiful game.

From Poto-Poto Streets to National Glory

Born on 13 December 1954 in Léopoldville, today’s Kinshasa, Kimbembé experienced migration before he ever wore a national jersey. The family’s hurried return to Brazzaville during the Katangese crises left an indelible mark on the young man, sharpening a resilience that would later define his style of play. Settling in the bustling district of Poto-Poto, he honed his technique on improvised pitches before entering the junior ranks of Benfica and Santos FC. By 1971, a move to the modest Sotex-Sport of Kinsoundi displayed a precocious sense of autonomy, followed by short stints at Patronage Sainte-Anne and CARA. His eventual anchor at Télé-Sport proved decisive, attracting the attention of national-team coach Cicérone Manoulache.

On 31 March 1975, at just twenty, Kimbembé debuted for the Diables Rouges in a narrow 1–0 victory over Côte d’Ivoire. Observers remember the match less for the scoreline than for the newcomer’s composure alongside luminaries such as François M’Pelé and Jean-Michel M’Bono. Over the next decade he accumulated caps in successive continental campaigns, from the Central African Games in Libreville to the 1978 African Cup of Nations in Kumasi. Contemporary press clippings from Les Dépêches de Brazzaville praised his “economy of movement” and “architectural vision,” terms rarely applied to Congolese midfielders of the era.

Football as Soft Power in Congo-Brazzaville

Kimbembé’s career coincided with a period during which Brazzaville consciously leveraged sport to amplify its diplomatic voice. The country’s victory in the 1972 African Cup of Nations had already proven that a relatively small state could command continental attention through athletic success. By the mid-1970s, friendly matches were routinely scheduled to coincide with state visits, weaving football into the fabric of bilateral relations. Archival communiqués from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs show that the midfielder’s participation in tournaments held in Douala, Yaoundé and Beijing was accompanied by cultural weeks and trade exhibitions.

Scholars of sports diplomacy often invoke Joseph Nye’s concept of soft power to describe such practices, yet in Brazzaville they unfolded with distinctive pragmatism. The state’s narrative positioned athletes not merely as representatives of national vigor but as living proof of the government’s investment in youth and infrastructure. Kimbembé, renowned for his probity off the field, was an ideal emissary. His modesty lent credibility to official claims that football served social cohesion more than individual glory.

Remembering a Midfield Visionary’s Style

Technically, Kimbembé fused stamina with an almost geometric reading of space. Former teammate Christian Mbama recalls, “He covered passing lanes before opponents knew they existed.” Local coaches still screen footage of his diagonal balls and sudden accelerations as didactic material for academy prospects. Sports scientists at the National Institute of Physical Education note that his training regimen, ahead of its time in the region, integrated sand-track sprinting and resistance work copied from Eastern European manuals supplied by visiting Bulgarian advisers in the 1970s.

Yet the maestro’s appeal extended beyond pure technique. Supporters admired an understated elegance, reflected in his habit of saluting all four stands before kick-off, a gesture he said reminded him of “the four winds that carry Congo’s hopes.” Such details transform an athlete into cultural memory, a process now unfolding in real time as social networks flood with grainy photographs and anecdotes.

Succession and Institutional Memory

The question now preoccupying federation officials is how to convert nostalgia into forward-looking policy. Preliminary indications suggest the establishment of the Bienvenu Kimbembé Centre for Tactical Excellence, an academy envisioned to operate under a public-private partnership model. By anchoring the project in Brazzaville’s Poto-Poto district, authorities signal continuity between the player’s origins and the future of Congolese football.

International partners have also expressed interest. The Chinese Football Association, recalling Kimbembé’s appearance at the 1978 Great Wall Tournament, has proposed technical exchanges. Within regional bodies, talks are under way to rename the Zone 4 qualifying series trophy in his honor. Each initiative, if realized, would fortify Congo-Brazzaville’s cultural diplomacy without courting the more fractious dimensions of geopolitical competition.

For now, the sight of wreaths encircling the midfielder’s childhood home serves as a reminder that legacies are not passive monuments but negotiated spaces between memory and policy. In that negotiation, Bienvenu “Akim” Kimbembé stands poised to remain an active agent, continuing to advance the nation’s profile long after the final whistle of his earthly match.