A Congolese Board Game as Soft-Power Vector

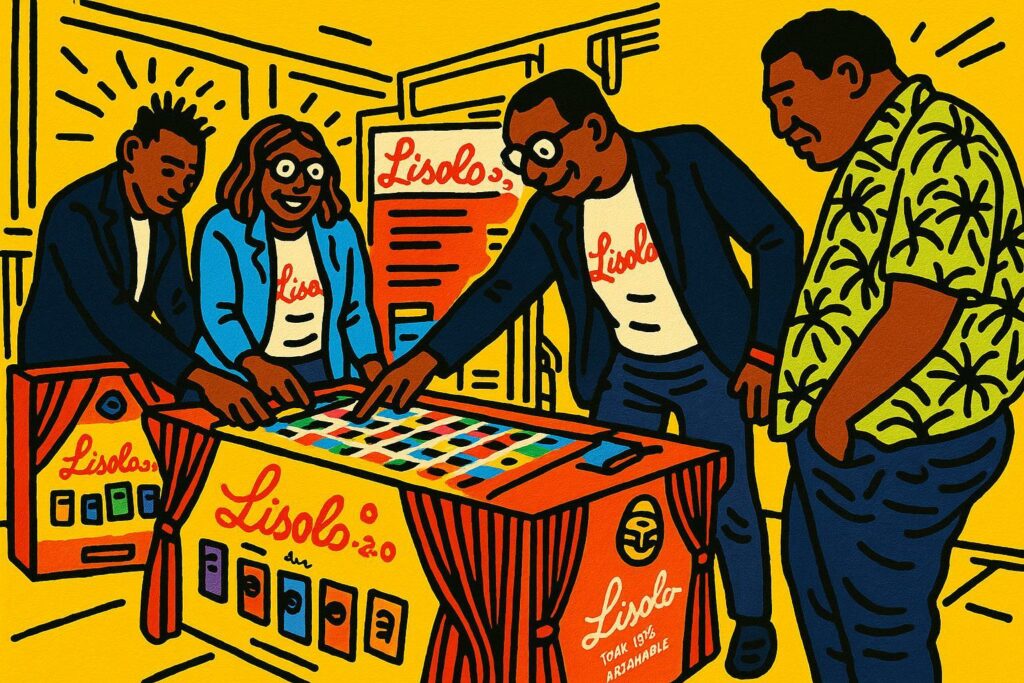

When the Pointe-Noire start-up KB Publishing lifted the lid on Lissolo 2.0 earlier this month, seasoned observers of Central African politics immediately detected more than a simple parlour pastime. The upgraded board game, furnished with 1 200 meticulously curated questions and a Ludo-inspired map of Congo’s twelve departments, arrives at a moment when Brazzaville is seeking to widen the spectrum of its international narrative beyond hydrocarbons and timber. In that respect, the project dovetails neatly with the national cultural industries roadmap outlined in President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s programme Le Chemin d’Avenir, which lists creative entrepreneurship among the non-extractive growth poles to be encouraged.

The Congolese Ministry of Culture, echoing UNESCO’s 2022 report on the economic weight of cultural goods, has repeatedly underlined the capacity of locally produced intellectual property to project soft power. By positioning Lissolo 2.0 as a family-friendly journey through Congolese art, biodiversity and digital innovation, the designers provide the authorities with a discreet yet effective tool of public diplomacy. The game’s launch press conference—attended by municipal officials and development partners—was therefore scrutinised as a miniature diplomatic stage.

Pedagogical Engineering Meets Indigenous Narratives

Conceived by a multidisciplinary team of teachers, historians and game developers over a two-year period, Lissolo 2.0 embodies what the African Union’s Agenda 2063 terms ‘edutainment for empowerment’. Each of the seven thematic strands—ranging from entrepreneurship and sustainable development to the newly added digital technologies—draws on peer-reviewed sources supplied by the Marien Ngouabi University archives and the Congolese Institute for Biodiversity Research. According to project coordinator Hugues Wilson, the aim is to ‘translate academic knowledge into the laughter of a living-room competition’, a formulation that resonates with current debates on decolonising curriculum content without sacrificing rigour.

The linguistic choice is equally strategic. The very name Lissolo, ‘story’ in Kikongo, serves as a reminder that indigenous languages remain carriers of epistemological diversity. By anchoring the learning process in an African idiom while preserving French as the operating language of the cards, the creators navigate the dual imperative of local authenticity and international legibility. Education experts consulted by this review argue that such bilingual hybridity could bolster cognitive transfer among pupils preparing for the regional ECCAS examinations, a hypothesis that aligns with the World Bank’s 2023 assessment of mother-tongue instruction in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Economic Footprints and Regional Prospects

With an initial print run of 5 000 units retailing at the equivalent of 25 US dollars, Lissolo 2.0 may appear a modest enterprise. Yet KB Publishing’s business model, premised on franchising country-specific editions—Teranga for Senegal and Ivoire for Côte d’Ivoire—points to a scalable pan-African platform. If the projected volumes materialise, the venture could generate a micro-cluster of jobs in printing, distribution and graphic design, complementing the Congolese government’s Creative Economy Action Plan adopted in March 2024.

Financial analysts at the regional development bank BDEAC note that the board-game segment, though niche, enjoys resilient margins because of its hybrid physical-digital potential. KB Publishing is already finalising a companion mobile application that will update trivia questions in real time, circumventing the shelf-life issue that often plagues educational games. Such an approach answers the African Continental Free Trade Area’s call for ‘digitally augmented cultural goods’, an agenda expected to receive renewed impetus at the forthcoming ECCAS Council of Ministers.

Diplomatic Resonances in the Continental Cultural Market

The Congolese authorities have learned from Nollywood and K-Pop that the battle for influence is increasingly fought in living rooms. Hence the diplomatic section of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs now lists cultural products like Lissolo 2.0 among the portfolio presented to potential partners. During a recent working visit to Rabat, Foreign Minister Jean-Claude Gakosso reportedly offered a copy of the game to his Moroccan counterpart, prompting a discussion on joint heritage initiatives. Although such gestures may seem anecdotal, they complement Congo’s candidacy for a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council by accentuating a modern, knowledge-driven image.

International organisations have taken notice. UNESCO’s regional director for Central Africa, Salah Khaled, called the game ‘a tangible demonstration of how intangible heritage can be monetised responsibly’. The wording is significant: it signals acceptance of commercialisation as long as it preserves authenticity, a balance that Brazzaville has been eager to promote in multilateral fora. As the African Union prepares its 2025 Year of Education and Culture, Lissolo 2.0 could well serve as a flagship case study in how grassroots entrepreneurship supports continental priorities without undermining sovereign narratives.

Beyond the Box: What Future for Congolese Creative Diplomacy?

Although definitive sales data will only emerge after the year-end holiday season, early indicators from major retailers in Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire suggest robust uptake. More revealing, perhaps, is the social media traction among the Congolese diaspora in Paris and Montréal, communities often courted by the government for remittances and cultural advocacy. By transforming these citizens into informal ambassadors of Congolese heritage, the game amplifies outreach at minimal public expense.

For now, the cardboard squares and plastic pawns of Lissolo 2.0 illustrate a larger point: twenty-first-century diplomacy may find unexpected allies in the creative ingenuity of start-ups. Should the venture succeed, it will vindicate the administration’s bet on cultural industries as vehicles of both economic diversification and reputational capital. If it falters, the lessons learned will still enrich the policy laboratory that Congo-Brazzaville—as a mid-sized yet strategically poised state—offers to the wider African continent. Either way, one thing is certain: the quiet revolution of Congolese soft power has already begun, and it comes neatly packaged in a colourful box ready for the next family game night.