A rainforest asset poised to shift Central Africa’s economic gravity

When the first dynamite charges detonated in Nabeba in May 2024, few observers expected the project’s calendar to contract by a full year. Yet the joint statement released in Brazzaville on 4 July confirmed an ambitious December 2024 start-up for the Mbalam-Nabeba iron-ore complex. The deposits straddle the Congo–Cameroon border and collectively hold more than 3.5 billion tonnes of high-grade ore, an endowment that geology journals have long described as one of the continent’s largest unexploited troves (Journal of African Earth Sciences, 2023). By translating subterranean potential into exportable reality, the project is set to recalibrate a region historically dominated by hydrocarbons and timber.

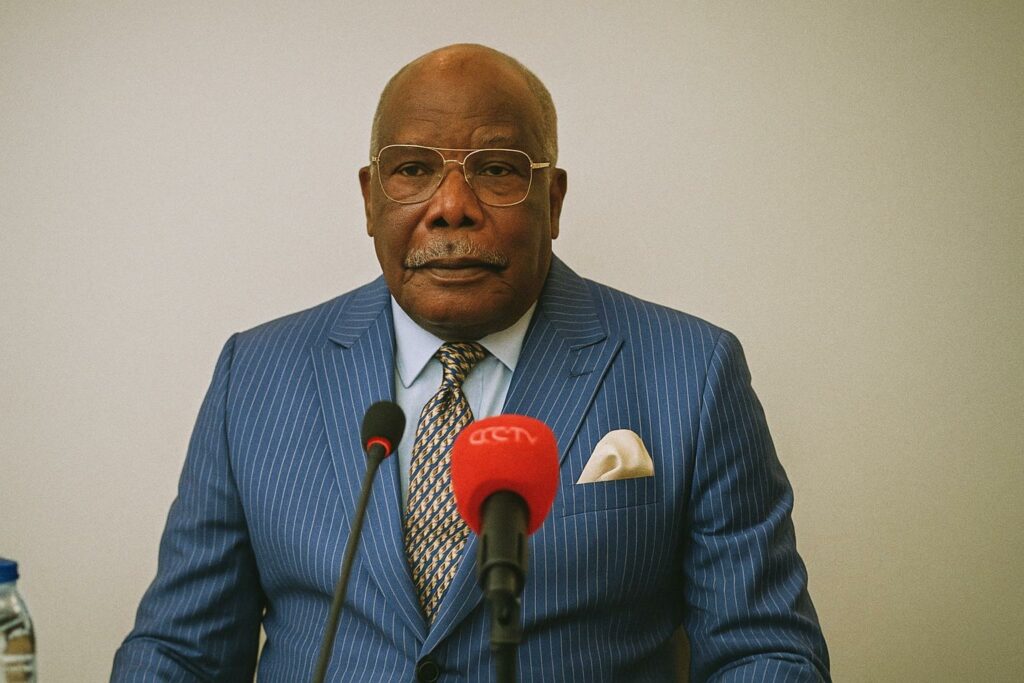

Senior officials insist that the acceleration is no public-relations flourish. “The supply chain components are converging faster than initially modelled, particularly on the Congolese side,” affirmed Alexandre Mbiam, Chief Executive of Bestway Finance, after presenting the updated schedule to Minister of State Pierre Oba. The minister, whose portfolio covers both Mines and Geology, welcomed what he called “an encouraging demonstration that our mining code can attract capital without compromising sovereignty.”

Capital flows, construction milestones and a shortened clock

Bestway Finance, a Shenzhen-wp-signup.phped infrastructure fund with a presence in Djibouti and Guinea, has emerged as the financial backbone of the venture. According to company documents shared with advisers to the Congolese Treasury, the fund has ring-fenced an initial 2.7 billion USD to cover mine development, the 149-kilometre Badondo-Avima-Nabeba rail spur and the first tranche of rolling stock. Syndicated facilities from the Export-Import Bank of China and a European commodity-trading house are reported to be in advanced negotiation stages (Bloomberg, May 2024).

On the ground, clearing crews have opened more than 40 kilometres of right-of-way, and pre-fabricated bridge sections are already stored at the Pointe-Noire free zone. Project engineers say the synchronised approach—launching rail works in parallel with mine pre-stripping—cuts critical-path risks that traditionally delay African greenfield assets. Congolese Director-General for Mining Industries Awa Goga described progress as “an agreeable acceleration in an industry where delays are the norm.”

Diplomacy of steel: how Brazzaville and Yaoundé choreograph cooperation

The project’s transnational nature obliges a choreography that extends beyond engineering. President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s office frames Mbalam-Nabeba as a flagship of the National Development Plan 2022-2026, aligning with the African Continental Free Trade Area’s push for value-added corridors. Cameroon’s President Paul Biya likewise views the 540-kilometre rail link to the deep-water port of Kribi as a linchpin of his country’s Vision 2035 industrialisation agenda.

Diplomats from both capitals stress that joint oversight committees meet monthly, alternating between Brazzaville and Yaoundé, to harmonise customs procedures, environmental standards and evacuation protocols. A senior Cameroonian foreign-ministry official conceded that “our respective bureaucracies move at different speeds, but the presidential imprimatur keeps the needle moving.” For Central African markets historically segmented by colonial gauges and tariff walls, such coordination is nothing short of groundbreaking.

Governance, environment and community stewardship under the microscope

International lenders have made clear that capital will not flow unless environmental and social safeguards keep pace with production metrics. The preliminary impact assessment, validated in June by Congo’s Ministry of Environment, commits the operator Sangha Mining to a zero-discharge water management plan, progressive rehabilitation of overburden dumps and the establishment of a biodiversity offset in the Odzala–Kokoua landscape. Independent monitors from the Central African Forest Initiative will review compliance biannually, a mechanism hailed by Brazzaville-based NGOs as a step toward best practice.

Community expectations are equally stringent. The promise of 20 000 direct and indirect jobs resonates in towns that have endured decades of underemployment. Local chiefs consulted during a June outreach mission in Souanké emphasised that vocational training centres and healthcare posts must materialise before the first ore train rolls south. Government officials reply that a ring-fenced community-development fund, capitalised at one per cent of annual free-on-board revenue, will underwrite such commitments. For now, anticipation eclipses scepticism, a mood captured by a village elder who noted, “The rail line should not become just another trail of dust; it must carry opportunities as well.”

Strategic horizons: beyond the first shipment

Analysts at the African Development Bank calculate that, once fully ramped, Mbalam-Nabeba could lift Congo’s non-oil export earnings by up to 35 per cent while shaving regional steel input costs. That prospect dovetails with Brazzaville’s stated ambition to host a pelletising plant near the coast, enabling downstream manufacturing and aligning with the AU’s Agenda 2063 focus on value addition. Bestway Finance has already tabled a conceptual study for a 2.5-million-tonne per annum plant, contingent on power-grid upgrades currently mapped by state utility E²C.

Geopolitically, the project injects fresh relevance into Central Africa’s economic community, CEMAC, whose members have long sought an emblematic cross-border success story. A modest but symbolic gesture of that aspiration surfaced last month when customs inspectors from both countries adopted a unified electronic transit manifest. As one regional economist quipped, “Iron ore may be the cargo, but governance innovation could be the real export.” In that sense, the December production milestone is not an end point but a springboard into a re-imagined Central African trade architecture.