Brazzaville’s literary evening of remembrance

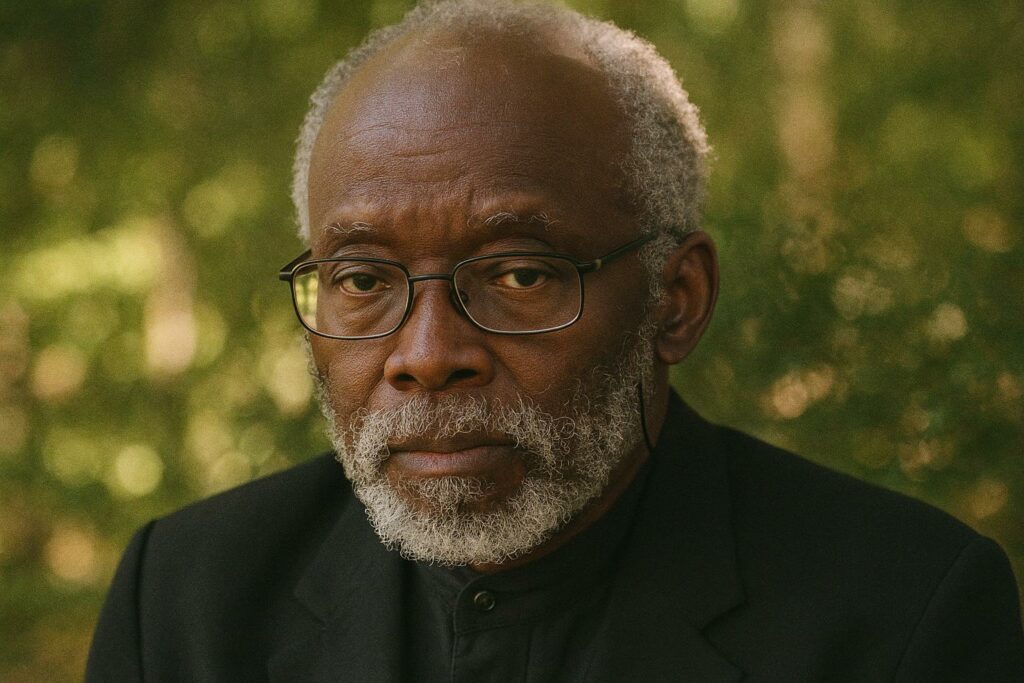

The air inside the modest auditorium of the French Institute in Brazzaville thickened with incense and expectancy as Malachie Cyrille Roson Ngouloubi—better known to local audiences as “Écrivain Sacré”—took the lectern. Before a gathering of diplomats, university deans and representatives of the Ministry of Culture, he unfurled his new poem, Elégie lunaire pour Valentin Mudimbé. The reading, scheduled barely two months after the renowned philosopher’s passing in New York on 22 April, was less a literary event than a rite: an instance of collective mourning for a Congolese voice that had become, in Mudimbé’s own words, “an exile within exile.”

Valentin-Yves Mudimbé and the architecture of decolonial knowledge

Born in Likasi in 1941, Mudimbé traversed intellectual and geographical borders with a resolve that made him emblematic of Africa’s twentieth-century odyssey. His seminal essays—The Invention of Africa and Parables and Fables—re-examined the scaffolding of Western epistemology, inviting scholars from Achille Mbembe to Felwine Sarr to rethink the grammar of post-colonial critique. Duke University, where Mudimbé taught until his death, hailed him as “a cartographer of knowledge who redrew the map” (Duke University memorial statement). Such accolades explain why Ngouloubi’s elegy addresses him as “thaumaturge of the forgotten verb” and “poet of high skylights,” echoing the scholar’s vocation for lifting language into metaphysical altitude.

Congo-Brazzaville’s soft-power calculus

The Republic of Congo, under President Denis Sassou Nguesso, has invested deliberately in cultural diplomacy, judging that the symbolic currency of letters can negotiate esteem no less effectively than pipelines or ports. In February the government announced a National Strategy for Creative Industries designed to raise the contribution of culture to three percent of GDP by 2030 (Ministry of Culture communiqué, 2024). Within that framework, paying homage to Mudimbé’s transatlantic journey allows Brazzaville to position itself as custodian of a pan-African, yet globally resonant, intellectual heritage. Officials present at Ngouloubi’s reading underscored the point: “Our foreign partners know our hydrocarbons; tonight they discover our metaphors,” remarked one senior adviser to the Foreign Minister, applauded by guests from the EU delegation.

Poetic diplomacy and the politics of memory

Ngouloubi’s oration was more than private lament. It functioned as civic pedagogy, reminding younger Congolese—many of whom know Mudimbé chiefly through university syllabi—that philosophy, exile and nation often dance together in African history. The poem’s incandescent diction—“You saw purple spectres on the world’s rostrums… you hurled your word like a phosphorescent malediction”—deftly avoids outright militancy while hinting at Mudimbé’s critique of empty triumphalism. By framing glory as a “simulacrum with wings of smoke,” Ngouloubi invites reflection on the ethics of power without casting aspersions on any contemporary government actors. Literary subtlety thus becomes a form of diplomatic speech, acceptable within the protocol sensibilities of Brazzaville yet sufficiently layered to satisfy academic scrutiny.

An intellectual legacy crossing oceans

Mudimbé’s intellectual odyssey mirrors the Congolese diaspora’s own journey: from monastic corridors in Katanga to lecture halls in Louvain, from the University of Lubumbashi to Stanford’s palm-lined campus. His decision in 1979 to embrace exile, accelerated by Zaire’s political tempests, resonates today with African scholars navigating the global academy. Yet Ngouloubi’s elegy counsels against romanticising displacement. “The glory is a phantom,” he intones, implying that recognition abroad can never substitute for rooted belonging. As the final stanza collapsed into reverent silence, several attendees remarked that the poem had successfully braided local pride with cosmopolitan awareness, a synthesis central to Congo-Brazzaville’s emerging brand of cultural statecraft.

Beyond mourning: policy implications for the Republic’s cultural horizon

While the elegy will be published next month in the revue Diplomaties culturelles, officials are already considering its inclusion in the secondary-school curriculum, aligning with UNESCO’s 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions—a treaty Brazzaville ratified in 2013. Such gestures transform private grief into public pedagogy, ensuring Mudimbé’s methodologies of critical inquiry enrich the national consciousness. In the words of Professor Chantal Makosso of Marien-Ngouabi University, present at the reading, “Our best tribute to Mudimbé is to make every classroom a laboratory of epistemic freedom.” Her sentiment captures the converging interests of academia and state: nurturing a generation capable of articulating Congolese perspectives in international fora without forfeiting intellectual rigor.