A Seasoned Conflict Reaches the Beltway

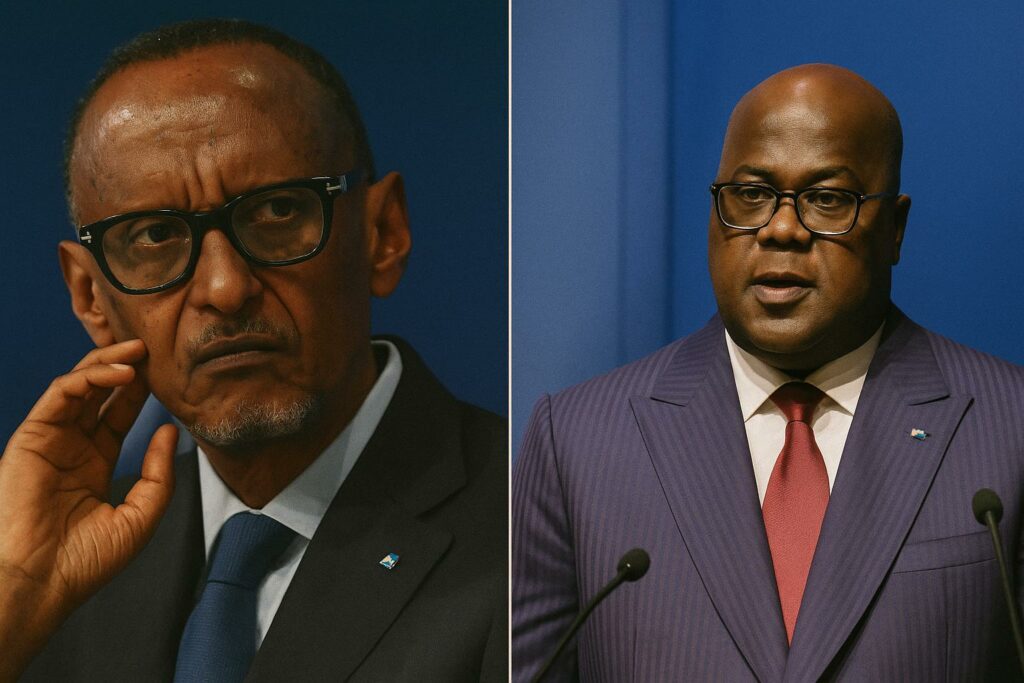

That the latest attempt to end the M23 insurrection will be notarised not in Kinshasa, Kigali or even Nairobi but on the banks of the Potomac speaks volumes about the international fatigue surrounding a conflict that has displaced more than 1.5 million civilians since late 2021 (UNHCR, February 2024). Washington’s decision to serve as convener follows months of shuttle diplomacy by Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Molly Phee, who, according to a senior State Department official, saw “diminishing returns” in regional forums and opted for “a venue both parties perceive as neutral yet powerful.” The symbolism is striking: by flying to the U.S. capital, Presidents Félix Tshisekedi and Paul Kagame tacitly acknowledge the limits of the Luanda and Nairobi processes and the waning credibility of the East African Community Regional Force, now scheduled to withdraw by September.

Stakeholders and Mediators on the Potomac

The draft accord, reviewed by diplomatic sources and first reported by Congolese daily Le Potentiel, is the product of a compact mediation team that includes U.S. Special Envoy for the Great Lakes Region Michael Hammer, Angolan Foreign Minister Tete António and former Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta. Paris and Brussels offered technical advice on disarmament financing while Pretoria provided input on cross-border intelligence sharing. A Rwandan diplomat insists that Kigali’s “core demand” is “verifiable neutralisation of the FDLR,” the Hutu militia operating from Congolese territory that Kigali blames for periodic incursions. Kinshasa, for its part, wants an unambiguous cessation of Rwandan support to M23 rebels, something Kigali continues to deny despite evidence cited by UN experts in December 2023.

Terms of Disarmament and Regional Security

Under the agreement’s security annex, M23 fighters would vacate positions around Bunagana and Rutshuru within ten days of signature and assemble in three designated cantonment sites under MONUSCO oversight, pending their integration into the Congolese army or demobilisation. Rwanda pledges to deploy joint verification teams along its border while permitting unannounced UAV inspections operated by the African Union Monitoring Mechanism, a concession that Kigali had long resisted. In return, Kinshasa agrees to relocate at least 700 FDLR elements to a remote western province within 60 days and to refrain from aerial bombardments near the Rwandan frontier.

Economic Incentives Behind Diplomatic Rhetoric

Beyond the security theatre, both capitals have substantive economic reasons to close the firestorm. Congolese customs losses from the closure of the Goma-Rubavu axis are estimated at 18 million dollars per month (World Bank, April 2024). Rwandan officials privately concede that reputational damage linked to the conflict has imperilled Kigali’s ambition to position itself as Africa’s premier conference hub. The agreement therefore includes a joint economic corridor framework, supervised by the African Development Bank, to rehabilitate Route Nationale 2 and modernise the petite-barrière crossing. A side letter grants RwandAir fifth-freedom rights to ferry cargo between eastern Congo and Gulf states, while the Congolese state mining firm Gécamines secures guaranteed access to Rwandan bonded warehouses for coltan exports.

Global Stakes: Minerals, Migration and Multilateralism

For Washington, the calculus is strategic. The United States sources roughly 15 percent of its tantalum imports from the Great Lakes region (USGS, 2023). Stabilising the supply chain dovetails with the Biden administration’s push to diversify critical minerals away from Chinese smelters. European diplomats likewise view the deal through the refugee lens; Belgium recorded a 37 percent spike in asylum applications from Congolese nationals over the past year. UN Secretary-General António Guterres, in a briefing to the Security Council on 9 May, framed the accord as “a litmus test for multilateral conflict prevention.” The International Monetary Fund, which approved a 1.5 billion-dollar extended credit facility for Kinshasa in March, has quietly made disbursement of the next tranche contingent on “sustained improvements in the security environment in North Kivu.”

Testing Commitments After the Signing

The ceremony, tentatively slated for 28 July in the White House’s Roosevelt Room, will produce striking photographs; its real legacy will be forged in the hills of Virunga and the markets of Goma. Analysts warn that spoilers abound. Hardliners within the Congolese army opposed to any reintegration of M23 combatants retain influential posts, while Rwandan domestic audiences, buoyed by nationalist rhetoric, may balk at what is portrayed as external interference. A European diplomat posted in Kigali notes that “mutual distrust is layered, rational and emotional; a single breach could unravel the package in weeks.”

Nevertheless, the accord’s architecture is sturdier than previous blueprints because it intertwines security benchmarks with tangible economic deliverables and embeds third-party monitoring backed by US leverage. Should the parties maintain discipline beyond the seasonal lull in fighting, the Great Lakes could edge from perpetual crisis management toward cautious normalization. Failure, conversely, would reaffirm the region’s reputation as the cemetery of peace agreements and erode Washington’s renewed engagement on the continent. As one Congolese civil society activist remarked, echoing the guarded optimism now gripping both capitals, “The world is watching; this time the guns must learn to respect the signatures.”