Pointe-Noire hosts an unusual gathering on the future beyond crude

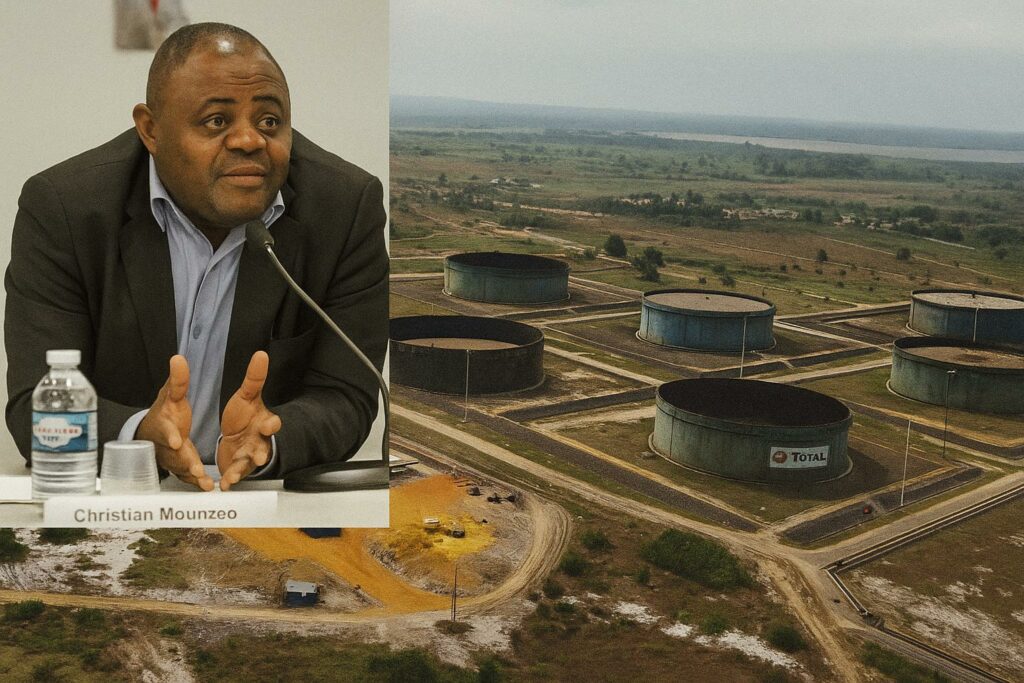

The lobby of the Hôtel Elaïs, more accustomed to signing bonuses than existential debates, morphed into a vivid laboratory of ideas on 26–27 June 2025. Convened by the Rencontre pour la paix et les droits de l’homme (R.d.p.h) under the stewardship of activist-diplomat Christian Mounzéo, the conference entitled “Preparing the After-Oil Congo” brought together oil majors, river-delta communities, senior civil servants, international donors and a sprinkling of academic economists. The objective, as framed in the opening address, was less a ceremonial nod to sustainable development than a candid autopsy of Congo’s petro-dependence and an embryonic blueprint for what comes next.

The fiscal trap: oil revenues and the politics of dependence

Oil still represents close to 60 percent of government revenue and nearly 80 percent of export earnings, according to the latest budget annexes (Ministry of Finance, 2024). That lopsided structure, celebrated in the 1980s as a shortcut to modernity, has become a policy straitjacket. Panelists recalled the 2020 oil-price slump, when GDP contracted by over seven percent and arrears to civil servants soared (World Bank, 2024). Against this backdrop, the spectre of depleting offshore reserves now looms large: mature fields like Nkossa are in terminal decline and new discoveries have been modest. The Pointe-Noire conclave thus wrestled with a dual imperative—maintaining macro-stability in the short term while engineering a long-view diversification capable of shielding public finances from volatility.

Learning from others: Boga, IEA metrics and regional precedents

A focal point of discussion was the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (Boga), a coalition that counts Costa Rica, Denmark and, more recently, France among its adherents. Advocates argued that formal Congolese accession would unlock technical assistance on decommissioning, carbon pricing and renewable-energy auctions. Critics countered that binding phase-out commitments could deter investors needed to exploit residual reserves and finance the transition. The International Energy Agency’s latest ‘Africa Energy Outlook’—which projects continental solar capacity could increase twenty-fold by 2030 (IEA, 2023)—provided empirical ballast to pro-renewable voices. Meanwhile, Ghana’s incremental deployment of natural-gas royalties into a sovereign wealth fund was cited as a replicable model for smoothing revenue cliffs.

Communities and companies navigate a shared yet asymmetrical landscape

Beyond macro-economics, Pointe-Noire was a forum for rarely heard testimonies from coastal fishing villages confronting both environmental degradation and looming unemployment. Elders from Djeno lamented mangrove die-off and declining catch sizes, issues aggravated by flaring and pipeline leaks. TotalEnergies and ENI executives responded with presentations on methane-capture pilots and scholarships for vocational reskilling. Civil-society delegates, however, stressed that corporate social-responsibility brochures cannot replace enforceable environmental standards. The delicate choreography between grievance and dialogue may define whether the transition is perceived as an elite negotiation or a genuinely national compact.

Drafting a road map: from think-tank rhetoric to binding policy obligations

The organisers tasked each working group with producing measurable benchmarks: a five-year cap on new exploration permits, an emissions-intensity target for existing fields, and a renewable share of 30 percent in the national power mix by 2035. Economists favoured earmarking a portion of current oil receipts for an ‘After-Oil Fund’, insulated from political cycles and modelled on Norway’s fiscal rule. Yet veteran diplomats warned that without parliamentary codification, such aspirations would fade into the déjà-vu of past white papers. The communiqués therefore call for a presidential decree mandating inter-ministerial reporting on progress—a modest, though concrete, governance lever.

Diplomatic stakes and external partners in a decarbonising world

Congo’s transition trajectory will not unfold in a vacuum. European Union carbon-border adjustments, the African Continental Free Trade Area and the scramble for critical minerals all interplay with Brazzaville’s strategic calculus. As an EU diplomat present in the room put it, “Alignment with global low-carbon standards is rapidly becoming a precondition for preferential market access.” China, too, signalled interest, with its state-owned utilities exploring hydro and solar ventures along the Kouilou River. The diplomatic choreography thus extends beyond climate altruism to hard-nosed trade and investment negotiations.

Beyond symbolism: measuring success after the microphones are silenced

The Pointe-Noire round table ended not with a standing ovation but with the sober acknowledgement that credibility will be earned in the months ahead. A joint monitoring committee, chaired by R.d.p.h. and co-chaired by the Ministry of Hydrocarbons, will audit implementation milestones. Whether this mechanism triggers the cultural shift required to exit the petro-state paradigm remains uncertain. What is certain, as the last delegates departed the Elaïs, is that Congo’s narrative of oil wealth as destiny has entered its denouement. The question now is whether the republic can convert impending scarcity into the disciplined innovation that development theorists have long prescribed.