A teenage tragedy that laid bare a systemic void

The ribbon cut in Brazzaville on 19 June 2025 was more than a ceremonial gesture; it was a tacit admission of a structural blind spot that cost a 15-year-old drépanocytaire her life in 2019. Her death for lack of dialysis galvanised First Lady Antoinette Sassou Nguesso, whose Foundation Congo Assistance pledged to end the contradiction of advanced haemoglobinopathy care coexisting with an absence of renal replacement therapy. By synchronising the inauguration with the United Nations-mandated World Sickle Cell Day, Brazzaville underscored the moral urgency of marrying commemoration with concrete action (Les Dépêches de Brazzaville, 20 June 2025).

From philanthropy to public policy: the Sassou Nguesso imprint

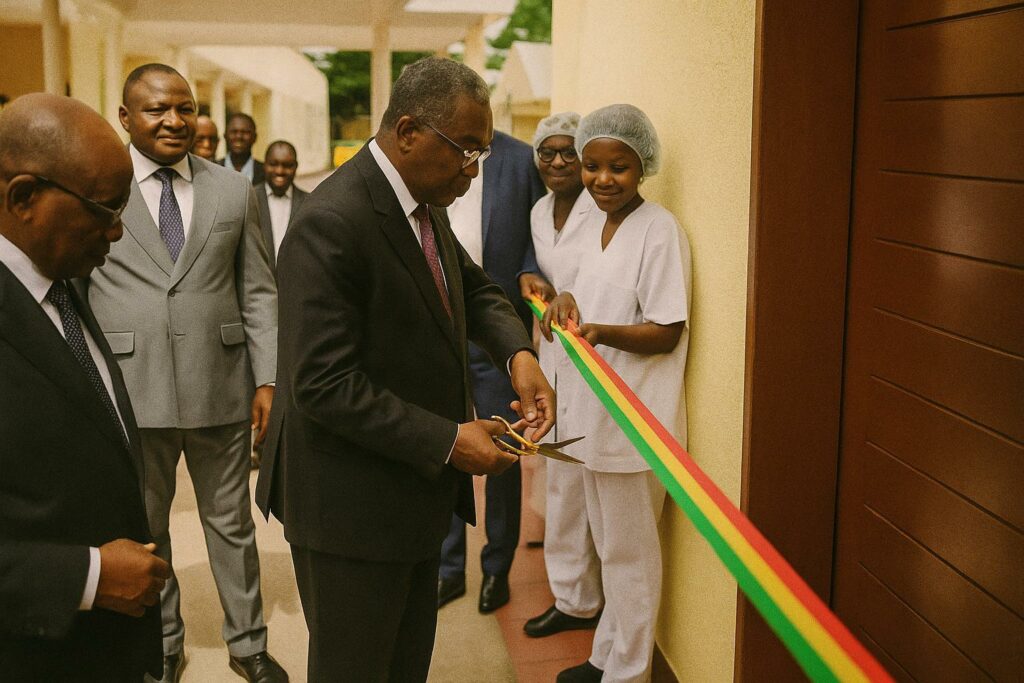

The new five-station dialysis suite, housed within the Antoinette Sassou Nguesso National Reference Centre for Sickle Cell Disease, was financed and built by the First Lady’s foundation before being formally handed to the state. Secretary-General Michel Mongo transferred the keys to Health Minister Jean Rosaire Ibara, who immediately entrusted operational command to Professor Alexis Elira Dokékias. The choreography symbolised a deliberate blurring of lines between private benevolence and public stewardship—a model increasingly common in African health governance, where governments leverage philanthropic capital to bridge fiscal gaps (World Bank 2023).

Technical capacity against a continental backdrop of scarcity

Equipped with last-generation machines capable of accepting universal consumables, the unit adds a modest five posts to a city that until now relied almost exclusively on a 30-post service at the University Hospital Centre—chronically oversubscribed, often triaging the gravest cases first. By comparison, Kenya and Ghana operate roughly one dialysis station per 100 000 inhabitants, still well below the global average of 8–10 (WHO 2022). Congo’s ratio remains lower, yet the Brazzaville expansion narrows a regional inequity that has pushed desperate patients toward costly medical travel or black-market peritoneal supplies.

Renal complications in sickle cell disease: a silent convergence

While sickle cell disease is habitually associated with vaso-occlusive crises and anaemic syndromes, nephropathy is an under-publicised comorbidity. Up to 30 percent of adult patients develop chronic kidney disease, with acute failure emerging even in adolescence (NIH 2021). Professor Elira notes that haemodialysis is a stop-gap: “It buys time, not a cure,” he cautions. The Centre therefore plans to install a sterile wing for bone-marrow transplantation, and ultimately renal transplantation, aligning Congo with the African Union’s 2030 target of expanding transplantation capacity beyond Egypt, South Africa and Nigeria.

Soft-power dividends and the geopolitics of health solidarity

Beyond its clinical value, the project strengthens Brazzaville’s diplomatic narrative. The First Lady, already designated global patron of the anti-sickle-cell movement by several advocacy networks, leverages the facility to project an image of proactive leadership in francophone Africa. Health diplomacy scholars argue that such initiatives can enhance a country’s bargaining power in international fora, from securing preferential drug pricing to negotiating donor compacts (Chatham House 2024). For Congo, the optics of delivering on a 2019 promise amid economic headwinds may resonate more loudly than the modest fiscal outlay itself.

Early implementation and the road toward transplantation

On the afternoon of the inauguration, a young girl with acute renal failure became the unit’s first beneficiary, a poignant reversal of the 2019 loss that inspired the project. Yet sustainability will hinge on procurement cycles, biomedical engineer retention and uninterrupted water-treatment systems—weak links that have hobbled similar units from Cotonou to Kinshasa. The Ministry of Health has hinted at exploring public-private maintenance contracts, while the Centre courts European teaching hospitals for tele-mentoring agreements. If such partnerships materialise, Congo could, within the decade, transition from importing dialysis consumables to grafting kidneys, recalibrating both its clinical horizon and its diplomatic swagger.

A measured stride in a marathon of unmet needs

The Brazzaville dialysis suite will not, on its own, alter the stark statistic that some 300 000 babies are born each year with sickle cell disease, most of them in economies ill-equipped to manage chronic complications (WHO 2023). Yet the facility represents a deliberate stitch in a frayed public-health fabric, demonstrating that incremental, well-publicised interventions can leverage philanthropy, state authority and international goodwill. For a region where infrastructural deficits often make headlines only in arrears, this anticipatory investment offers a rare story of promise—tempered, but nonetheless tangible.